It's generally quite easy to guess the etymology of an English place name, and quite pleasant too, as you get to sound clever. The system is not in the slightest bit infallible, but it generally works. So long as nobody has

The Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names to hand, nobody will be able to contradict you, and that's the important thing.

So, here is a quick cheat sheet, and I shall explain at the end why it doesn't always work.

Elements

English place names tend to have two elements, perhaps three if they're feeling important. The last element is the important one because it tells you what the place actually was. For example,

ton meant farm in Old English. So if the place name ends

ton, then way back in the fogs of time it was a farm.

The first element is basically an adjective. Often it's just a physical description. So

Norton is

North Farm.

Sutton = South Farm

Easton = East Farm

Weston = West Farm.

Not insanely complex.

So, here is a quick and incomplete list of final elements.

Borough = Fortification

Burn/Bourne = Stream

Bury = Manor or estate, i.e. a big farm

By = Viking town (that's why they're only in the North in the old Danelaw)

Chester/caster/cester = Roman fort

Cot/coates = Cottages

Ley/leigh/ly = Clearing in a forest

Don = Hill

Den = Woodland or valley (or, sometimes, a wooded valley)

Ham = Home (or sometimes it means land that stretches out into a river)

Hurst = Wooded hill

Ing = Family land (-

ing means that the first element is definitely someone's name. It's often compounded to -

ington or -

ingham or somesuch. So

Birmingham is

Beorm's family's home)

Sea = Island, or a bit of dry ground in the middle of a marsh

Ton = Farm

Ware = Weir

Wick/wich = Market. To be more precise wick is a market or a very specialised farm. It means that an industry was concentrated there. Whether Chiswick was a cheese factory or a cheese farm or a cheese market is hard to say. But we do know that Chiswick was cheesy, as was Keswick, and that Gatwick contained many goats.

Worth = Enclosure i.e. there was a fence up to keep out the wolves and the Welsh and other furry creatures of the night.

First Elements

The first element is a description.

The first element can be physical. I hope that

Up- is self-explanatory. Or there's

chal/chil, which means

cold. Sometimes it refers to a nearby physical feature. Underhill or Exmouth should both be clear, provided you've heard of the river Exe.

Often, the first element an animal or a plant.

Shepton is obviously a

sheep farm. But often the animal can be a little hidden. For example

Swin = Swine = Pig. So

Swinton is

Pig Farm.

Houn =

Hound =

Dog.

Craw =

Crow. So when you see a first element just wonder vaguely to yourself whether it sounds roughly like a common animal.

Musbury, Musgrave, Muscoates and Muston were all infested with mice.

The same thing happens with the plants. The Old English for Oak was

Ac, so

Acton is Oak Farm.

Lind is

Linden tree (or

lime tree as we usually call it). Poplar is poplar.

But the main thing to remember about the etymology of English place names is that they're mostly very, very boring, because they are named after people. These are not important people. It's just that once upon a time there was a guy who owned that farm or that clearing or that weir. So people called it after him. And so some Anglo-Saxon lives on forever. This accounts for most place names.

Well, to be honest, I've never done a full study. But I just opened the

Dictionary of Place Names at a random page and found that of the 22 entries, 11 were called after people, including Chilbolton which was a farm that belonged to Ceolbeald.

So, to dash around North London:

Finchley is a clearing in a forest (a

ley) that was once filled with finches, but

Wembley? Well, there isn't any animal or plant that sounds much like

Wemb, so you could guess that it was

Wemb's clearing, and you'd be pretty much spot on. It was

Wemba's clearing, which means that those football supporters who sing about Wemb-a-ley, are etymologically correct.

And there you have it. Look at the last element. Ask yourself whether the first element sounds like a plant or an animal or some physical description. Otherwise assume that it's the name of some Anglo-Saxon chap. You'll be right about three quarters of the time.

It is time for the destruction of error

I'm afraid that even a medium sized blog post like this cannot make you immediately infallible.

You may well be wrong. There are three main reasons for this.

1) Sometimes names just change over time for no good reason. There's a place in London called Aldgate. Anybody who knows anything about Old English can tell you that that means

Old Gate. But it doesn't. Originally it was called Alegate (

beer gate, presumably because beer was sold there). And then in the late Medieval period a D somehow insinuated itself and took up residence.

2) What looks like on thing is in fact another. There's a place in London called Brixton, which, using this method would come out as something like Mr Brix's Farm. In fact, the older records have it down as Brigga's Stone.

3) Sometimes something completely different comes in. A property developer can think up a nice sounding name. Baron's Court in West London is precisely that. The developer just wanted it to sound as posh as Earl's Court, which is the area next door. Further out, there's Richmond. It's only called that because the Duke of Richmond built a palace there. So really it's named after Richmond in Yorkshire, which is hundreds of miles away. (Since you ask, Richmond in Yorkshire is

Rich Mount from the Norman French).

The only way to be sure, is to consult a copy of the

Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names. The writers of that have gone back to the Doomsday book etc and actually checked. But as very few people carry one around, you can always get away with a bit of specious speculation using the above method. Plus, it makes road signs mildly more interesting.

P.S. I've used the term "English" here because, obviously, none of this works for a Celtic place name. It would have confused things. The prefix

Kil- means

calf in English and

Church in Celtic. Mind you, there are English place names all over the British Isles, and lots of Celtic place names in England. The Celts survived here, and where they lived the preface is

Wal-, which was the Old English word for foreigner.

P.P.S. Through all this I'm missing out words that are the same in modern English like

Church or

Ford or

Bridge. You should have worked out what Newton means by now. And if you can't work out what Newcastle is then you're either very silly or very clever.

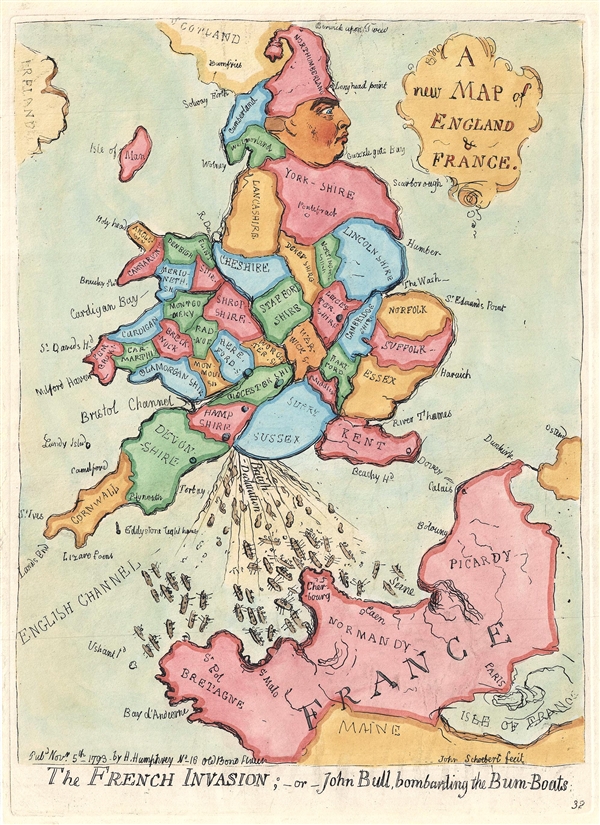

This map should now make sense