No man is an island, although I confess I am becoming a peninsula.

No man is an island, although I confess I am becoming a peninsula.The Latin for island was insula, and something that was almost an island was a peninsula. Therefore when people needed a posh word for turning something into an island (these necessities arise), the English word insulation was invented. Originally, it literally meant turning into an island. In 1854 you could, with a straight face, write:

The insulation of peninsulas by the destruction of the isthmus which previously connected them with the mainland.

Then insulation started to mean anything that cut something off from the outside, and started to be applied to electricity and central heating. You could also talk about people being insular, if they lived on islands and were a tad unfriendly.

In the 19th century there was a German fellow called Paul Langerhans. Paul started cutting people open and discovering things. He discovered the Langerhan cells in the skin, and then the Langerhan layer (also in the skin), and then he looked in the pancreas and found little islands of cells that are called the islets of Langerhans. Then he moved to Madeira, became insular, wrote a guidebook and developed an unhealthy interest in sea worms.

Anyhow, the islets of Langerhans also have a technical Latin name: insulae pancreaticae. And the important chemical that they produce is therefore called insulin

All of these words were invented by clever fellows who knew Proper Latin. But in Italy, when the Roman Empire declined and fell, they forgot Proper Latin and started to speak Sloppy Latin or Italian as it is now known.

In Sloppy Latin they stopped pronouncing the N in insula and so insulatus became isolato, and the French nicked that and got isolé, and the insular English nicked that and got isolated. Later we decided that this adjective needed a verb and noun so we invented isolate and isolation. These are just the Sloppy Latin version of insulate and insulation.

The very odd thing is that none of these words are etymologically related to island. Island isn't Latin at all. It comes from Middle English yland, and that comes from Old English igland. The silent S got added a lot later, presumably in confusion.

Anyhow, back in the day (by which I mean Medieval and Early Modern times) whenever a reasonably well-off fellow died, his family would run down to the church with a bit of money and pay to have the bell toll. Other reasonably well-off people would hear this and they would send a servant to see who had gone to join the majority.

Which brings us to lovely and lamentable prose of John Donne's Devotions on Emergent Occasions, Meditation XVII:

No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as any manner of thy friends or of thine own were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

So go and wash your hands.

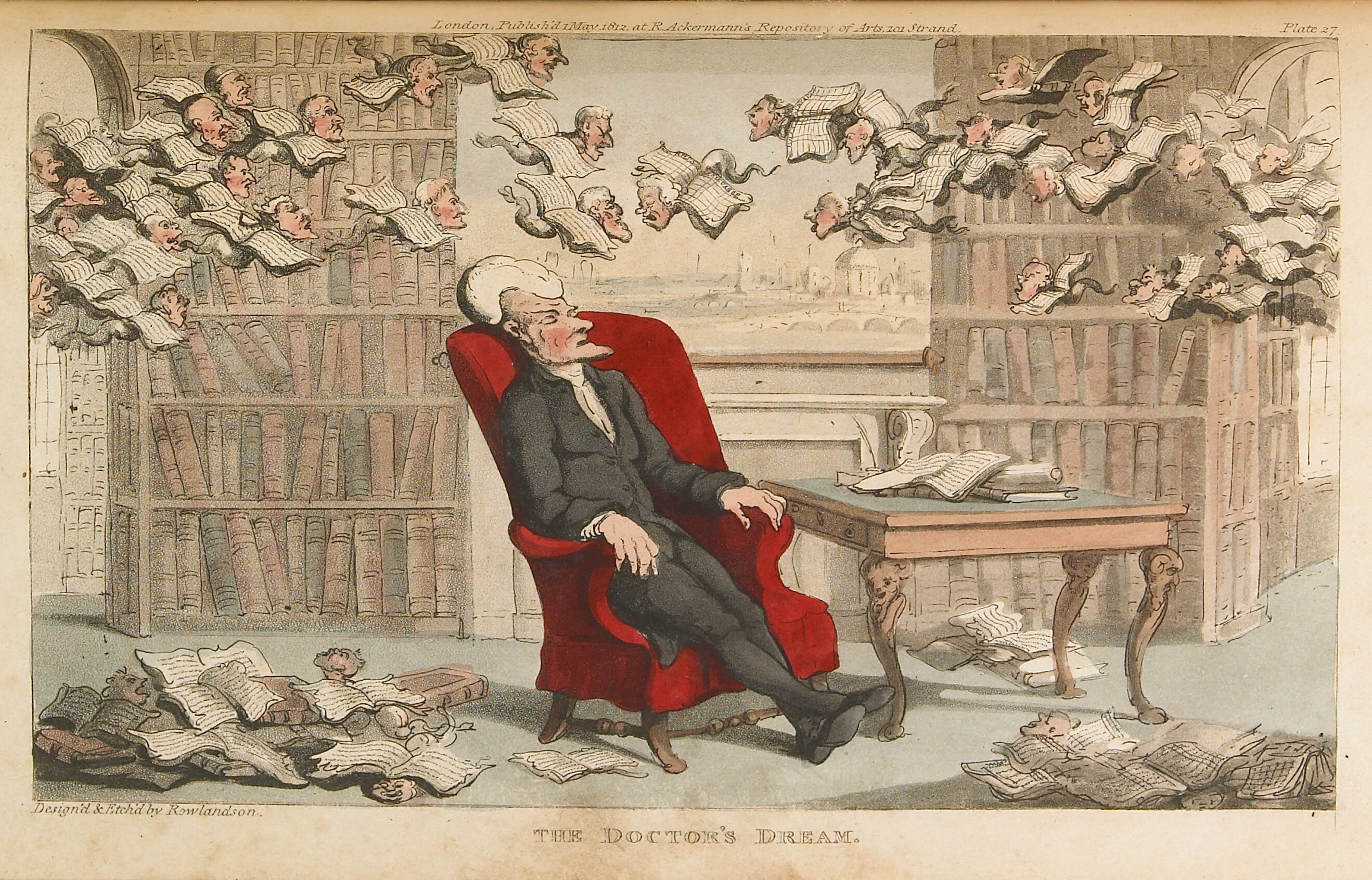

Paul Langerhans contemplating sea-worms.